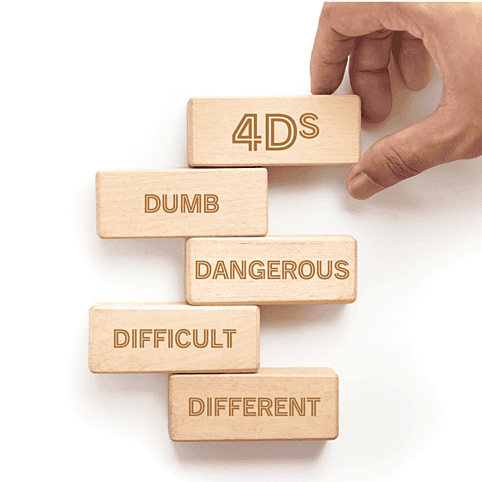

An Introduction to the 4D's from Jeffery Lyth

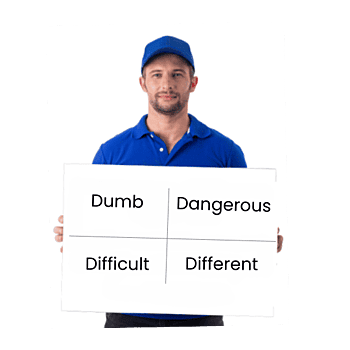

DUMB (Sense Making/Frustration)

The word ‘dumb’ may not always be the best choice, but it can be useful in starting conversations about things that don’t make sense. In today’s diverse and informed workplaces, leaders must pay attention to how people understand their tasks and environment.

Shared understanding doesn’t just happen—it needs to be encouraged.

Weick and Sutcliffe describe sensemaking as the process of giving meaning to experiences. It’s about looking back and making sense of what people are doing.

Leaders should actively ask how people make sense of things and encourage them to speak up when something doesn’t add up. This helps both the leader and the team work more effectively.

DANGEROUS (Risky/Challenging)

DANGEROUS (Risky/Challenging)

DIFFICULT (Hard/Demanding)

When a work task is difficult or demanding, many will simply just ‘soldier on’ and ‘make do’, possibly assuming that difficulty is just the nature of the task. But task difficulty can be an important sign that the task is being done incorrectly or that something is amiss elsewhere in the system.

DIFFERENT (Change/Surprise)

Why use the 4D's

Enhanced Communication and Engagement

Proactive

Risk Management

Bridges the Gap: Work As Imagined and Work As Done

Encourages a Culture of Learning Over Blame

Promoting a Psychologically Safe Culture

Practical Application of the HOP Principles

- Error is a consequence of an event and a symptom of system complexity, degrading controls or brittle system rules.

- System, work design, and conditions in work need to support normal everyday work.

- Blame degrades psychological safety, silences the voice of workers to share about work, and prevents learning from happening.

- Leaders can listen and learn from the outcomes of the 4Ds, and lead the organization in sustainable improvement.

- Learning supports change at the worker, workgroup, and organizational levels, which drives the improvement of better work and better operational outcomes.